My parents told me I was going to college. End of discussion. You see, college had been out of my parents’ grasp, but they made sure it was not out of mine. So, I went. Reluctantly at first. I did not know what I was getting into, and I struggled to make sense of this new world. I can remember those moments I cried because it all seemed overwhelming. Eventually though, I found my place, and college opened up a whole new way of thinking to me--critical thinking--that I really was not aware of before. I gained the ability to read the world around me and to seek the knowledge I needed in various situations.

Fast forward a bit. I graduated, got married, and had two beautiful children. I lived in a happy bubble, but in June 2012, I found myself in the deepest, darkest moment of my life. My son, who was 2 ½ at the time, was diagnosed with a brain tumor. I did not know for 24 hours whether my son would live or die. Every critical thinking skill I had gained was pertinent at this point. Over the next three months, my husband and I had to make enormous decisions that impacted our child’s well-being--from which hospital to go to, which procedures to allow, when to question the doctors, and when to rely on their expertise. My critical thinking skills allowed me to read medical information, ask questions, and consider options.

Why did I have to wait until college to develop these thinking skills? What if I had not gone to college? Where would I have been in this situation with my son? When reflecting on my experiences, I know there is no time to waste with my students. I want them to begin developing this skill set now, not later. I’m not sure all of them will have the resources necessary to attend college. So I must teach my students now how to think, how to research, and how to question what they do not understand. We all have students on different levels--those who need the challenge of being “pushed up” and those who need scaffolding in order to be “pulled up”. As a Language Arts teacher, I began to explore the idea of student choice in writing to promote the real-world skills that students need. This year, my students chose their own driving question for two different writing assignments--an informational speech and an argumentative piece.

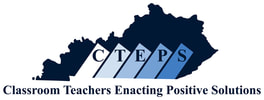

The outcomes I saw when I moved away from “everybody responding to the same prompt” were phenomenal. From the very beginning, students were intrigued with choosing their own writing focus. In the informational speech, students began with an “I Wonder” question. There was a part of me that believed students would ask simplistic questions, but that fear quickly dissipated when I saw what students were wondering: How can we know this is reality? What is the best way to go about training rescue dogs? Why can we not achieve world peace? How can I become better at passing a football? Below is an example of a student’s original brainstorm on the paper I provided (figure A).

When I asked my students if I should assign the “I Wonder” speech next year, Kendall, one of my high-performing students stated, “Yes, I highly recommend you assign this to your future 6th graders! I think they will very much enjoy writing their speeches on what they have interest in. It will bring out their inner selves on what they know and like. I predict that they will love it and do very well on it.” The picture below shows Kendall presenting after she was chosen as a winner in her small group (Pic 1).

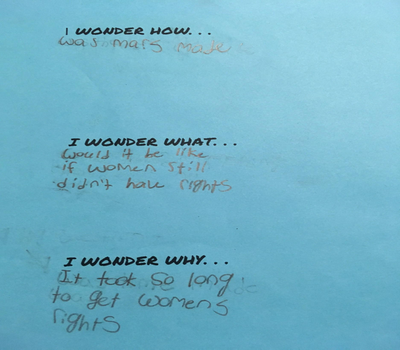

I was equally excited about the questions and then the claims students developed from their questions in the second writing assignment, an argumentative piece. They argued that society should do more for the mentally ill, there are better ways to find cures than animal testing, social media can help fight depression, and learning a foreign language can enhance the human experience. Below are examples of where students worked in groups to formulate their driving questions (Figure 2).

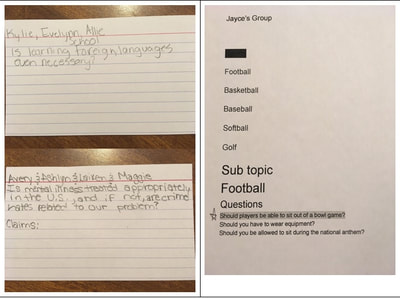

As Cailey, one of my intervention students who wrote on why cats should not be declawed, noted, this writing assignment was different because “all the others i have done in like 5th grade i have never chosen my own topic before” and “what i have enjoyed about writing this paper is you get to choose your own exciting topic.” What I quickly learned was I needed to throw my trepidation to the wayside and realize that students will rise to the challenge. Yes, even those students who we consider “struggling” learners. As the pie chart below show, almost 69% of students felt more excited about writing when they chose their own focus for their writing assignments (Graph 1).

I remember two moments in particular with struggling students this year; these moments were the ones that reminded me I need to push all of my students, as far and as high as they can go. I was already planning to expand student choice to all of my classes since I had started with the higher-performing class as a sort of pilot-program for student choice in writing. I began by having students read an article about same-gender schools, and I instructed students to state their opinions on the issue in small groups, as well as to identify something they did not know about the issue after reading the article. One of my students, Tristin, who often struggles to recall details from a story right after reading it, was more engaged in this discussion than he had ever been in anything else we had done in my class. He was animated, he was excited, and he could not wait to share his perspective with his classmates and comment on theirs. I wanted this student to have the opportunity to write about something he is passionate about. These students have things to say; we just have to provide the scaffolding and the platform for them to say it.

Damon, a student who enjoys the outdoors infinitely more than the classroom, first chose a writing focus that he ended up having little to say about. He thought it would work, but as I watched him struggle with reasons for his argument, I knew we had to do something different. I had gotten to know this student fairly well over the year, and I know he loves to build things and figure out how things work. I found an article for him on how schools should bring back shop class. Even though he was behind in the assignment, he went back and created another blog for his new article without me even prompting him to do so. Damon went on to write a paper that actually had some depth to it, providing evidence and commenting on the evidence. He had such a sense of pride and ownership of the paper, much more than in the prompt all of these students had responded to at the beginning of the year about how to deal with a bully. Read all of Damon’s paper here.

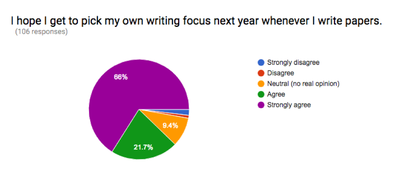

When students took information from their papers and turned them into presentations, both Tristin and Damon were chosen as winners in their small groups, and they then had the opportunity to present in front of the whole class. As the pie chart below shows, many of my students were more invested in their writing when they had a choice in what to explore (Graph 2).

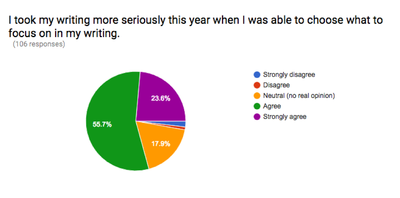

As teachers, giving all students the same writing prompt seems much more manageable and makes the content easier to cover. But when given the choice in their writing, students display more engagement and a sense of professionalism and ownership in the writing, both of which lead to greater depth in the final product--more evidence and more explanation. This is what we are all looking for from our students, right? Providing student choice is not a perfect process. It is often messy, but is is an overall stronger process because it is one that teaches students that they can find answers to what is important to them and to those things they feel they really need to know. As evidenced in the pie chart below, my students hope that they will have these same chances to find answers in the future (Graph 3)

Student choice is a process we can all implement in our classrooms. We must first allow students to wonder about topics and issues, then guide them to distinguish between easy-to-find answers and those that require more explanation, steps teachers can introduce students to in any classroom. We must remain flexible when not every student is on the same page (sometimes literally). We must seek out those around us who can help us take initial ideas and shape them into assignments that will benefit all students and who can help us stop and evaluate the progress in the middle when we are not seeing the results we want. And always, always, remaining cognizant of the fact that this is an imperfect process, a lifelong process, but one that is of infinite value. This is our opportunity for a writing lesson to become a life lesson in asking questions, finding answers, and formulating coherent responses--skills that my son, who is now 7 and plays every sport the doctors will allow, will need when he is in charge of monitoring his remaining health issues. It is these skills I want my students to leave my classroom and walk out into the world with (Pic 2 - My son, Andrew, at a recent Make-A-Wish event).

For more explicit information about providing student choice in writing, please visit Unbolted.

Fast forward a bit. I graduated, got married, and had two beautiful children. I lived in a happy bubble, but in June 2012, I found myself in the deepest, darkest moment of my life. My son, who was 2 ½ at the time, was diagnosed with a brain tumor. I did not know for 24 hours whether my son would live or die. Every critical thinking skill I had gained was pertinent at this point. Over the next three months, my husband and I had to make enormous decisions that impacted our child’s well-being--from which hospital to go to, which procedures to allow, when to question the doctors, and when to rely on their expertise. My critical thinking skills allowed me to read medical information, ask questions, and consider options.

Why did I have to wait until college to develop these thinking skills? What if I had not gone to college? Where would I have been in this situation with my son? When reflecting on my experiences, I know there is no time to waste with my students. I want them to begin developing this skill set now, not later. I’m not sure all of them will have the resources necessary to attend college. So I must teach my students now how to think, how to research, and how to question what they do not understand. We all have students on different levels--those who need the challenge of being “pushed up” and those who need scaffolding in order to be “pulled up”. As a Language Arts teacher, I began to explore the idea of student choice in writing to promote the real-world skills that students need. This year, my students chose their own driving question for two different writing assignments--an informational speech and an argumentative piece.

The outcomes I saw when I moved away from “everybody responding to the same prompt” were phenomenal. From the very beginning, students were intrigued with choosing their own writing focus. In the informational speech, students began with an “I Wonder” question. There was a part of me that believed students would ask simplistic questions, but that fear quickly dissipated when I saw what students were wondering: How can we know this is reality? What is the best way to go about training rescue dogs? Why can we not achieve world peace? How can I become better at passing a football? Below is an example of a student’s original brainstorm on the paper I provided (figure A).

When I asked my students if I should assign the “I Wonder” speech next year, Kendall, one of my high-performing students stated, “Yes, I highly recommend you assign this to your future 6th graders! I think they will very much enjoy writing their speeches on what they have interest in. It will bring out their inner selves on what they know and like. I predict that they will love it and do very well on it.” The picture below shows Kendall presenting after she was chosen as a winner in her small group (Pic 1).

I was equally excited about the questions and then the claims students developed from their questions in the second writing assignment, an argumentative piece. They argued that society should do more for the mentally ill, there are better ways to find cures than animal testing, social media can help fight depression, and learning a foreign language can enhance the human experience. Below are examples of where students worked in groups to formulate their driving questions (Figure 2).

As Cailey, one of my intervention students who wrote on why cats should not be declawed, noted, this writing assignment was different because “all the others i have done in like 5th grade i have never chosen my own topic before” and “what i have enjoyed about writing this paper is you get to choose your own exciting topic.” What I quickly learned was I needed to throw my trepidation to the wayside and realize that students will rise to the challenge. Yes, even those students who we consider “struggling” learners. As the pie chart below show, almost 69% of students felt more excited about writing when they chose their own focus for their writing assignments (Graph 1).

I remember two moments in particular with struggling students this year; these moments were the ones that reminded me I need to push all of my students, as far and as high as they can go. I was already planning to expand student choice to all of my classes since I had started with the higher-performing class as a sort of pilot-program for student choice in writing. I began by having students read an article about same-gender schools, and I instructed students to state their opinions on the issue in small groups, as well as to identify something they did not know about the issue after reading the article. One of my students, Tristin, who often struggles to recall details from a story right after reading it, was more engaged in this discussion than he had ever been in anything else we had done in my class. He was animated, he was excited, and he could not wait to share his perspective with his classmates and comment on theirs. I wanted this student to have the opportunity to write about something he is passionate about. These students have things to say; we just have to provide the scaffolding and the platform for them to say it.

Damon, a student who enjoys the outdoors infinitely more than the classroom, first chose a writing focus that he ended up having little to say about. He thought it would work, but as I watched him struggle with reasons for his argument, I knew we had to do something different. I had gotten to know this student fairly well over the year, and I know he loves to build things and figure out how things work. I found an article for him on how schools should bring back shop class. Even though he was behind in the assignment, he went back and created another blog for his new article without me even prompting him to do so. Damon went on to write a paper that actually had some depth to it, providing evidence and commenting on the evidence. He had such a sense of pride and ownership of the paper, much more than in the prompt all of these students had responded to at the beginning of the year about how to deal with a bully. Read all of Damon’s paper here.

When students took information from their papers and turned them into presentations, both Tristin and Damon were chosen as winners in their small groups, and they then had the opportunity to present in front of the whole class. As the pie chart below shows, many of my students were more invested in their writing when they had a choice in what to explore (Graph 2).

As teachers, giving all students the same writing prompt seems much more manageable and makes the content easier to cover. But when given the choice in their writing, students display more engagement and a sense of professionalism and ownership in the writing, both of which lead to greater depth in the final product--more evidence and more explanation. This is what we are all looking for from our students, right? Providing student choice is not a perfect process. It is often messy, but is is an overall stronger process because it is one that teaches students that they can find answers to what is important to them and to those things they feel they really need to know. As evidenced in the pie chart below, my students hope that they will have these same chances to find answers in the future (Graph 3)

Student choice is a process we can all implement in our classrooms. We must first allow students to wonder about topics and issues, then guide them to distinguish between easy-to-find answers and those that require more explanation, steps teachers can introduce students to in any classroom. We must remain flexible when not every student is on the same page (sometimes literally). We must seek out those around us who can help us take initial ideas and shape them into assignments that will benefit all students and who can help us stop and evaluate the progress in the middle when we are not seeing the results we want. And always, always, remaining cognizant of the fact that this is an imperfect process, a lifelong process, but one that is of infinite value. This is our opportunity for a writing lesson to become a life lesson in asking questions, finding answers, and formulating coherent responses--skills that my son, who is now 7 and plays every sport the doctors will allow, will need when he is in charge of monitoring his remaining health issues. It is these skills I want my students to leave my classroom and walk out into the world with (Pic 2 - My son, Andrew, at a recent Make-A-Wish event).

For more explicit information about providing student choice in writing, please visit Unbolted.

Danielle Burke taught high school English for several years before beginning her work as a 6th grade Language Arts teacher in 2012 at Boyle County Middle School. She holds a B.A. in English from Centre College and an M.A. in English from the University of Kentucky. She is currently a candidate for National Board Certification and is a graduate of the 2016-17 CTEPS team.